Parents who reciprocate their children’s negative emotions are less likely to find satisfying resolutions to conflict, according to new research from the University of California, Merced.

Parents who reciprocate their children’s negative emotions are less likely to find satisfying resolutions to conflict, according to new research from the University of California, Merced.

In a study published online today (May 5) in the journal Emotion, a team led by UC Merced Professor Alexandra Main combines observations with a novel statistical method to examine emotion dynamics between parents and adolescents during conflict discussions.

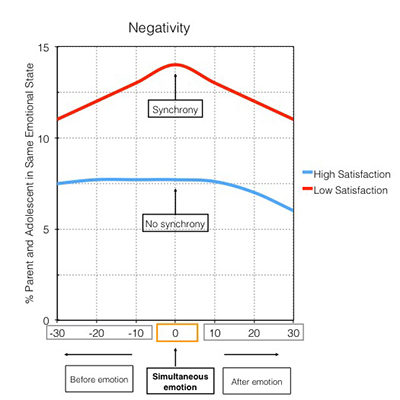

Main shows that when mothers and their adolescent children talk through conflicts, reciprocating each other’s negative emotions leads to less satisfying resolutions. She also found that with younger adolescents (ages 13-14), the mothers were typically the first to introduce negativity into the conversations; with older adolescents (ages 17-18), the adolescents were more likely to become negative first.

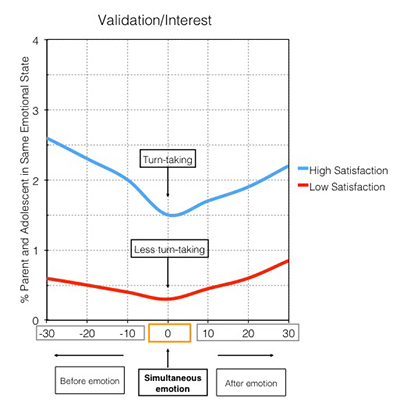

The study found that the most effective approach is for mothers to validate or show interest in their children’s points of view — and that this is only truly effective when the children validate their mothers in turn. This positive effect was not present if more than 30 seconds passed before a validation or interest was reciprocated.

“This suggests that it’s not just parental validation that is important during conflict, but that both parents and adolescents are given a chance to speak their minds and are heard by the other person,” Main said. “Using novel statistical techniques to analyze these interactions adds to our understanding of parent-child relationships and allows us to target more specific interventions for parents and adolescents struggling with conflict.”

Conversations Recorded and Analyzed

The study began four years ago, when Main was working on her dissertation as a Ph.D. student at UC Berkeley. Mothers and adolescents were recruited to participate in a lab study in which each pair discussed an issue of conflict in their relationship for 10 minutes. The conversations were recorded on video, and later “coded” second-by-second for 16 verbal and nonverbal variables to track each person’s emotions across each entire conversation.

The study began four years ago, when Main was working on her dissertation as a Ph.D. student at UC Berkeley. Mothers and adolescents were recruited to participate in a lab study in which each pair discussed an issue of conflict in their relationship for 10 minutes. The conversations were recorded on video, and later “coded” second-by-second for 16 verbal and nonverbal variables to track each person’s emotions across each entire conversation.

After completing her Ph.D., Main took a postdoctoral position and later joined the Psychological Sciences faculty at UC Merced. She and Professor Rick Dale, in Cognitive and Information Sciences, began discussing their mutual interest in social interaction. Dale and graduate student Alexandra Paxton — now a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute of Cognitive and Brain Sciences at UC Berkeley — helped analyze the results mathematically and visualize them in a series of charts.

Much of Dale’s previous work has involved using motion-tracking technology and computational software to gain insight into people’s mental activities. This was his first time using such methods to track emotion, and he said the results were among “the most amazing” he’s seen thanks to the design of Main’s study — a modification of a method previously used to study married couples — and the precision of the coding.

“You’re studying a really complicated system at a level that’s really hard to quantify,” Dale said. “But when you plug in the data, you get all these really elegant patterns of emotion with really precise timing.”

Paxton said the study was a major part of the UC Merced experience that helped prepare her for her current position and her future in academia.

“Interpersonal coordination — how people become more similar in behavior, cognition and emotion during conversation — is a driving perspective in my work, and looking at coordination during conflict is one of my passions,” Paxton said. “Naturally, when Professor Main approached us about this collaboration, I jumped at the opportunity.”

More Insights to Uncover

There will likely be more revelations to come from these recorded conversations, Main said. In a current project, students are coding the same videos for “disclosure” — tracking the points when children disclose personal things to their parents, and what the parents did in the moments immediately preceding those disclosures.

“Such understanding could help improve communication between parents and adolescents during a developmental period when children are seeking more independence from parents,” Main said.

She’s also looking to expand this work to different populations; while the initial study provided an ethnically diverse sample, most of the participants came from families of high socioeconomic status. In collaboration with Valley Children’s Hospital in Madera and UC Merced professors Deborah Wiebe and Linda Cameron, Main is conducting a similar study focusing on children and families coping with chronic illness.

She hopes to continue this work with underrepresented populations and immigrant families in the San Joaquin Valley, and she’ll likely do so in collaboration with the new Alliance for Child and Family Health and Development in Downtown Merced.

“I am really interested to see how this kind of study might play out in those groups,” she said. “There is not a lot of research that has looked into the dynamics of parent-child relationships in underrepresented populations.”