It’s estimated that a leaf-cutter ant colony can strip an average tree of its foliage in a day, and that more than 17 percent of leaf production by plants surrounding a colony goes straight into their giant, fungus-growing nests.

It’s no wonder these ants are considered the smallest recyclers on the planet and are referred to as "ecosystem engineers" by scientists because of the effects they have on the environment around them.

That’s why Professor Thomas Harmon, a founding faculty member with UC Merced’s School of Engineering and chair of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, and Environmental Systems doctoral student Angel Fernandez-Bou are studying the implications of leaf-cutter ants on soil CO2 dynamics in the tropical rain forests of Costa Rica.

“We’re focused on understanding the impact of a dominant member of the soil fauna, leaf-cutter ant Atta cephalotes, on soil CO2 dynamics in tropical rainforest ecosystems,” Harmon said. “We know little about the overall contribution of leaf-cutter ants to the carbon cycle.”

Their findings, published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences, could help inform studies of global carbon cycling.

Fernandez-Bou, the paper’s lead author, said they were curious about what happens in the nests.

“Why are these nests pumping out so muchCO2?” he said.

He and Harmon worked with an international research team at La Selva Biological Station, part of the Organization for Tropical Studies, to quantify the CO2 emissions coming out of those nests. The team started collecting data in 2015 and studied 24 different spots — nests, non-nests and abandoned nests — over the course of 2 1/2 years.

Some of these nests were large enough to fill a normal sized classroom.

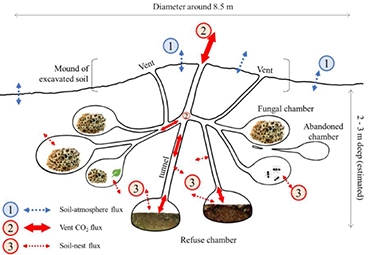

The study found leaf-cutter ant nests provide alternative transport pathways to release soil CO2 — increasing total emissions and decreasing soil CO2 concentrations. Air vents act like chimneys and push out an average of 10,000 times — and up to 100,000 times — more carbon dioxide than untouched soil, they discovered.

“The nests are a ventilation system, a pathway for CO2 to get out,” Fernandez-Bou said. “That’s the difference. The leaf-cutter ants change the concentration of CO2 through the vents.”

Harmon said the key to the study was in the measurements.

They needed an inexpensive, easy way to measure CO2, so Fernandez-Bou developed a solution that runs on a 9-volt battery and costs about $200 each. They trained students to use the devices in the field and got more data than would be possible with traditional, more expensive devices.

"If you measure the soil the traditional way, you are limited in how many measurements you can make each day, and there’s a big chance you will miss hot spots that may be a significant part of the emissions,” Harmon said. “No one has done something like this before; we are using a totally different approach to measure the flows and fluxes associated with CO2 emissions.”

The ants keep the soil open through vents in their nest, which leads to significantly more CO2 output compared to the forest without a nest. It is estimated that 1 percent of the forest has ants. They contribute nearly 0.5 percent of total forest carbon dioxide emissions.

“This figure could go higher as the leaf-cutters expand their habitat in response to warmer temperatures,” Harmon said, pointing out different species are also making an impact on carbon cycling — not just in the rain forests — in crops and parks too.

“We need to have a grasp on what other species are contributing while we manage the human parts of the problem. The number of hot spots could higher than we thought before and increasing over time, and we must take that into account,” Harmon said. “We’re in an era when we must account for and reduce carbon emissions.”